Both Wonderful and Strange: Remembering David Lynch

Ross Karlan, Director of Art Muse LA & Miami

You might say I am David Lynch obsessed. I regularly re-watch Twin Peaks, with cherry pie and black coffee, of course. I find Blue Velvet grotesquely beautiful and I assert that Lost Highway is excellent precisely because it doesn’t need to make sense. In college I explored the Philadelphia neighborhood colloquially known as the “Eraserhood” knowing that’s where he found inspiration as an art student. I do not consider Rabbits and What Did Jack Do to be deep cuts, but rather fundamental parts of his filmography. And, Mulholland Drive is unequivocally my favorite film of all time.

In many ways, David Lynch has shaped how I understand and think about art. As an undergraduate, I wrote my thesis on Mulholland Drive because I couldn’t shake the profound impact it had on me. The film was a puzzle I felt compelled to solve, and in the dozens of times I’ve watched it, I’ve continued to discover something new. At the heart of my thesis was the scene at Club Silencio, where the magician and singer Rebekah del Río force viewers to reconsider everything they’ve seen up to that point and, by extension, question the very nature of cinema itself. I saw this moment as a new-millennium version of René Magritte’s Treachery of Images, where all rules of semiotics are suspended. When the magician reminds us that “it is all an illusion,” we’re invited to recognize that cinema, too, is an illusion. Moreover, the entire film up to that point exists within an imagined or dreamed reality in Diane’s (Naomi Watts) mind.

The scene stuck with me as a sort of treatise or manifesto on perception, reality, and the act of making art and creating illusions to bypass our own reality. While explicit and intentional in the Club Silencio scene, the troubled balance between imagination and reality is a common thread throughout Lynch’s work. In Blue Velvet or Twin Peaks, for example, he even explores how outward-facing fabricated images really just mask a deep dark reality that lies just beneath the surface of a “picture perfect” world.

Little did I know, Lynch’s film and television was just the tip of the iceberg, and his fine art practice offered so much more to explore. In my senior year in college, 2014, I had the opportunity to see Lynch’s first major United States museum exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) — where he studied from 1965 to 1970 — and meet him, albeit briefly. The exhibition, David Lynch: The Unified Field, showed an enormous range of his work, from early student films he made, to sculptures, and paintings that became emblematic of his practice. The exhibition contextualized Lynch’s work across media, and showed how he, as an artist, always looked to push the boundaries of his materials and the messages he tried to convey.

The exhibition opened with Lynch's 1967 work Six Men Getting Sick, a multi-disciplinary installation that blends sculpture and film. The film itself is deceptively simple: a loop of six illustrated men vomiting after their stomachs fill with bright liquid. The soundtrack consists solely of a repeating siren, while the sculptural elements are integrated into the screen on which the film is projected. The stop-motion animation captures each frame, animating Lynch's own paintings. This installation had not been displayed since 1967, when Lynch was still a student, making its recreation for the public a rare treat.

Though the narrative is minimal—if it can even be called a narrative—and doesn’t seem to carry any overt meaning, Six Men Getting Sick established the tone for Lynch’s entire career. The work’s oddity and simplicity speak for themselves, creating the signature “Lynchian” mood that would become just as integral to his style as any plot.

Six Men Getting Sick also marked the beginning of Lynch’s painting practice, characterized by expressionistic, vignette-like moments that are as unsettling as they are bizarre. His use of choppy, textured brushstrokes evokes a sense of chaos, while his figures are often disfigured and grotesque. In some works, he incorporates body parts, eyes, mouths, and organs to challenge viewers' perceptions. Deeply influenced by Transcendental Meditation, Lynch’s painting process becomes an exploration of the subconscious and the dark psychological tensions tied to memory and emotion. Rock with Seven Eyes is a prime example, an eerie and grotesque image that grapples with sight, perception, and the subconscious through its repeated motif of the eye, layered with dark, unsettling textures.

As scholar Petra Gikoy-Hirtz1 notes, Lynch rarely explains his work or tries to assign it deeper meaning. His paintings, like his films, often tell stories—sometimes incorporating text and recurring characters such as "BOB," a figure who may or may not be the same BOB from Twin Peaks, the embodiment of evil. These works evoke Lynch’s cinematic sensibility, often feeling like isolated frames of a larger narrative. In Mister Redman, a mixed-media oil on panel, Lynch shows a small BOB beside a massive humanoid figure. The text reads, “Because of wayward activity based upon unproductive thinking, BOB meets Mister REDMAN.” The viewer is left uncertain about the story, or how BOB ended up here, but BOB’s “Oh no” conveys a sense of doom—perhaps with a hint of sarcasm.

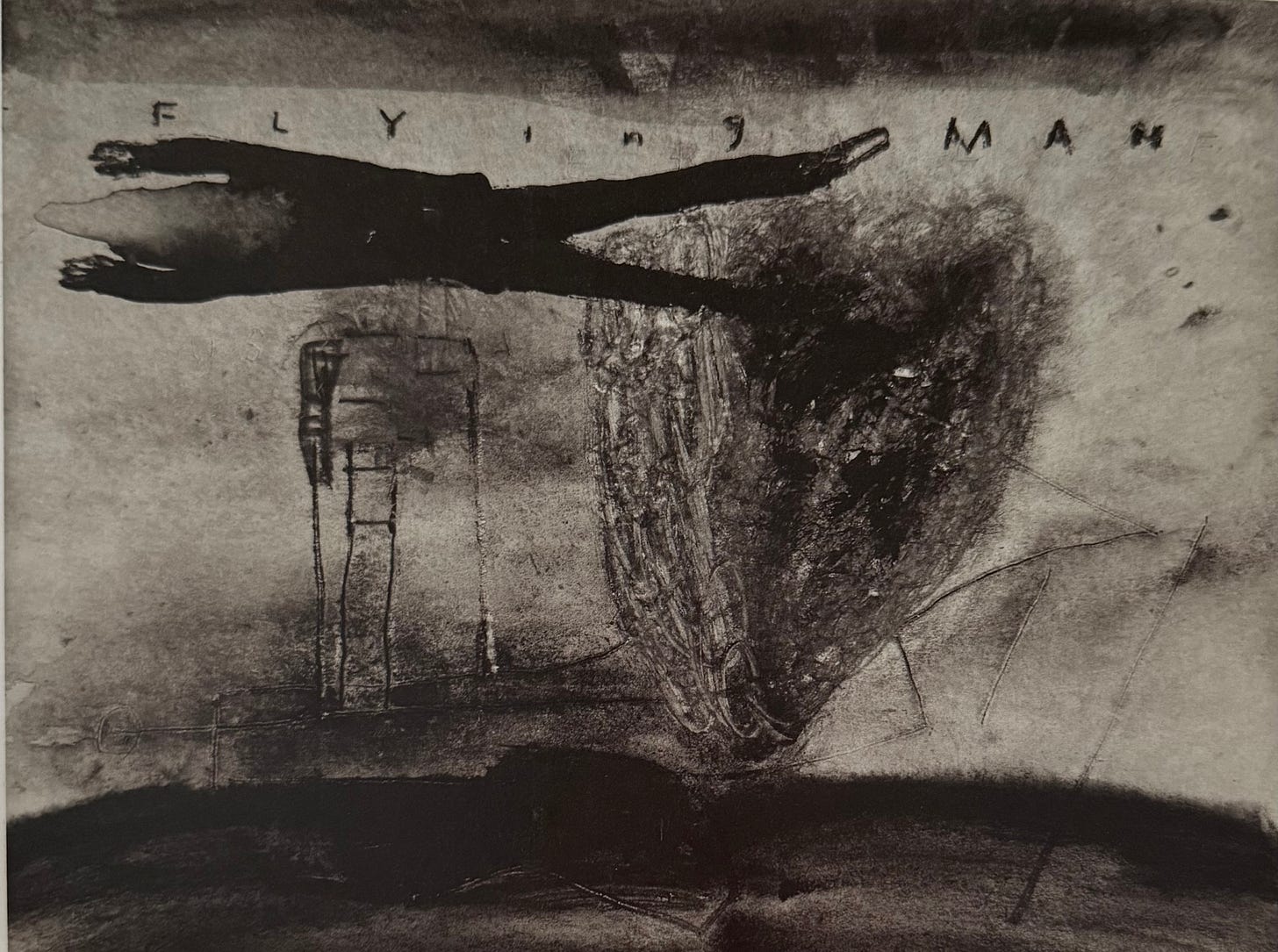

Smaller black-and-white works, ranging from watercolors to prints, capture the essence of the Lynchian aesthetic for me. It’s no surprise that Lynch’s career is framed by black-and-white films, starting with Eraserhead and concluding with the Netflix short What Did Jack Do? Works like Flying Man (a watercolor) and Man and Machine (a lithograph) stand out as precursors to Lynch’s exploration of black-and-white cinema in episode eight of Twin Peaks: The Return (2017). This episode—arguably the most artistic in terms of its aesthetic parallels to Lynch’s works on paper—reveals the dark forces controlling Twin Peaks, linked to the creation of the atomic bomb. The episode is a surreal journey that barely makes sense on a first viewing, but it remains a breathtaking example of Lynchian art. Hidden throughout are visual echoes of his paintings, such as the scene where the Giant floats through the air in a large theater, a moment that feels like a living embodiment of Lynch’s signature style.

In reflecting on Lynch’s films and visual art, it becomes clear how deeply his work has shaped my understanding of art. Lynch has consistently challenged us to question reality, perception, and the very nature of artistic creation. His refusal to explain or simplify his work invites us into a space of ambiguity, forcing us to confront our own subconscious and emotions all while he crafts worlds that are as perplexing as they are beautiful. For me, Lynch’s art is not just a series of films or paintings, but a lens through which to view the complexities of human experience, the tensions between reality and illusion, and the vast, uncharted territory of the subconscious. His loss is a profound one, but he is nevertheless a “damn fine” artistic master whose films and work I will return to over and over.

David Lynch: Someone is in My House. Prestel Press: 2018.

![S3E8] Golden Orb : r/twinpeaks S3E8] Golden Orb : r/twinpeaks](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lgpI!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe9eeb49b-caa1-4742-bbef-260975551a94_3840x2160.png)