Where the Streams Flow Together: The Art of Jeffrey Gibson

In the history of the United States Native Americans have been disproportionately marginalized; driven to the brink of extinction by American colonialism, their cultural survival and renewal is nothing short of miraculous. In a similar vein there are few groups more harangued by contemporary discourse than the LGBT+ community; nearly wiped out by AIDS in the 80’s and 90’s and currently under extreme pressure from the political Right, their resilience and cultural impact are incredible. Yet it is from both of these marginalized groups that an artist was chosen to represent the US in the 2024 Venice Biennale, one Jeffrey Gibson.

Born in Colorado in 1972, he descends from the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and the Cherokee tribe and is the first Indigenous-American to represent the US in a solo show at the Biennale. He grew up all over the world as his father was an engineer for the federal government and went to school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Royal College of Art. Bringing the long history of indigenous makers to the contemporary art world, he wants native people to be included in the larger story of art history and for them to be seen as a present people in the modern world. Gibson’s hybrid identity has helped him see connections between powwow regalia and drag fashion, between traditional dance and rave culture; and he wants to bring all of it, all of him, together in his work. By doing so he hopes to create a utopia for the future, a place where everyone is heard and appreciated for all parts of their identity. Something we desperately need in these troubled times. The show, currently on view at The Broad is entitled, The Space in Which to Place Me, and is set up exactly as it was in Venice.

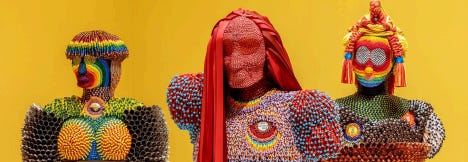

Each room in the show should be considered almost as a single work, with each individual piece like a line in a poem building to the whole. The second room one enters in the exhibition is painted yellow, on three of the walls are large kaleidoscopic canvases made of overlapping rainbow lines and triangles, in the center of each is a stylized text and found objects of traditional indigenous beadwork. In the center of the room is a dias with three portrait busts on pedestals, each made of elaborate multicolored beadwork and slightly abstracted around old political pins. The title and text of one of the large canvases (recently acquired for The Broad’s permanent collection) gives the central focus for the room and its works. It is called, The Returned Male Student Far Too Frequently Goes Back To The Reservation And Falls Into The Old Custom Of Letting His Hair Grow Long, a quote from a 1902 letter to Superintendent of Schools in Round Valley, CA from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. It speaks to the callousness with which American government officials treated native culture and people, as well as the resilience in indigenous people to maintain their way of life and fight back. Both of Gibson's parents had been sent to the mandatory government Indian schools where many died from ill treatment and malnutrition, making these pieces personal as well as historical works.

Including traditional beadwork alongside his modern interpretations connects Gibson with the legacy he grows from and brings those older crafts into the realm of art. The busts are meant to bring native people into the history of classical portraiture, while maintaining traditional crafts and aesthetics. The color palette Gibson uses is traditional to many native cultures today, who use modern beads from around the world to make their ceremonial clothing and traditional crafts. This mix of the traditional and the modern is central to Gibson's mission to have native people seen as existing and a part of the modern world, adding to it and getting inspiration from it. The hair styles don't belong to any specific tribe but echo many, and are meant to be gender and race unidentified, reaching towards the artists queer identity and the acceptance of that in many native cultures. The marble bases of the busts are meant to look like Southwestern Indigenous pottery, giving them a foundation in tradition; a history, and a source. The quote and the busts speak to the long history of the policing of culture in the US as well as the policing of gender expression, thus further connecting parts of Gibson's identity. The rainbows are part of native culture and a symbol for queer rights, the busts resemble the forms of warriors and drag queens.

The following room of the exhibition is painted a deep cobalt blue, rainbow ombre flags hang on the wall with stylized text in the center. In the middle of the room is a shiny red plinth with a bronze, life sized sculpture of a Native American on his horse, the real moccasins on the warriors feet have the title, I’m Gonna Run Every Minute I Can Borrow, beaded on the side. While the flags, plinth, and moccasins are new; the bronze sculpture was made in the early twentieth century by sculptor Charles Cory Rumsey and entitled, The Dying Indian. Intended to represent the inevitable death of all Indian people and culture after a century of genocide, and the stereotype of the noble savage. Gibson intervened in the work in 2019 commissioning John Little Sun (Pawnee/Cree) to make moccasins for the figure to wear. Done as an act of respect and care for the figure, individualizing the anonymous warrior and freeing him from empty stereotypes. The moccasins disrupt the narrative that indigenous people are all dying or dead, destined for extinction, and shows the living culture that survived and that thrives today. The quote on them is from a 1971 Roberta Flack song entitled, See You Then, and seeks to connect this ancient craft with the modern world, to show that the two flow together in current indigenous culture. The multicolored flags that encircle the statue are designed by the artist and are meant to represent the beauty of difference through their color and the affirmations at their heart. The room as a whole seeks to subvert and surround the western narrative about native peoples and their roles. It wants to create a new context that doesn't negate what came before but includes it within a greater whole to create a truer history for everyone. It is a reclamation of power both culturally and artistically.

The penultimate space in the exhibition has two gigantic figures in the center of a blue room, with Gibson's trademark rainbow patterns covering the wall behind them. The figures are made from ceramic, copper bells strung with rainbow fringe, and elaborate beadwork on the torso, shoulders, and collar. The presence these figures exude is palpable, the weight of the fringe tactile and they dominate one's memory of the show. They are meant as evocations of ancestral spirits, the heads recalling Mississippian effigy pots of the Southeastern US, the beads, bells, and fringe inspired by powwow regalia. Though powwows are now common among most tribes in North America they began a little over a century ago as a pan-indigenous cultural rebellion and response to the genocide of the colonisers. Dancing in artistic regalia for the ancestors and as a cultural revolt. The text in the mural behind them says, “we are made by history” a quote from Martin Luther King Jr. that urged his parishioners to actively forge their lives rather than be passively shaped by history. The figures stand between the viewer and those words and, symbolically, that power. On them are quotes from several major pieces of legislation. The Enforcer quotes the Reconstruction Acts that passed after the civil war to protect the rights of newly freed slaves, as well as the Enforcement Acts of 1870-71 which penalized interference with the right to vote. We Want to Be Free quotes the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 that made all native americans US citizens and granted equal protection under the law. None of this legislation would ever become a reality on the ground for decades if at all; and the figures stand for promises made and promises broken by the US government to Indigenous and Black people, showing the connections between their struggles. Gibson connects rebellion through dance and the individual DIY aesthetics of powwow culture to the rave and club/drag scene that queer culture uses for the same purpose. He uses the figures to connect the two lineages of ancestors, indigenous and queer, into towering figures of carnivalesque rebellion, cultural resilience, and possible bridges to a united, free future.

This future can be glimpsed in the video installation in the final room (also acquired by The Broad), where an indigenous woman, Sarah Ortegon Highwalking, dances in several jingle dresses of her own design to music by all native electronic dance music group, Halluci Nation. Originally displayed on sixty digital screens across Times Square all at once, the images of the dancer flip, squish and contort until they become variations on Gibson's abstract rainbow shapes all pulsing to the music. It is the perfect representation of the artist's mission, to bring traditional native culture and represent it as part of the contemporary world. To show both native and queer people beyond just trauma and imagine a utopia for everyone. Jeffrey Gibson stands as a living example of the possibilities of such a future and his art opens the doors for us to imagine too.