Up Close With Belkis Ayón at David Castillo Gallery

Ross Karlan, Director of Art Muse LA and Miami

Every once in a while an opportunity arises to experience an exhibition like no other. After leaving David Castillo Gallery’s current show Belkis Ayón —a solo show of the famous Cuban printmaker — I felt like I had an exclusive invitation into the artist’s mysterious and magical world. I was completely transported in a way that was unexpected and offered a chance to get up close and personal to Ayón’s beautiful work. While Ayón’s legacy has reached incredible heights in recent years, including an incredible traveling retrospective exhibition, Nkame in 2016 and 2017, the show at David Castillo is Ayón’s first commercial gallery show since her death in 1999.

While she has not quite reached the notoriety of other Latin American women artists, Belkis Ayón’s international fame has begun to take the world by storm, and the once relatively unknown and esoteric artist is slowly becoming more of a household name. Ayón was born in 1967 in a freshly post-Revolution Havana, Cuba. She was trained at the San Alejandro Academy and later at the University of the Arts (Instituto Superior de Arte) where she also taught. Ayón sadly died by suicide at the age of 32 in 1999, but despite her young age, her enormous impact on Cuban, Afro-Caribbean, and women artists continues her legacy.

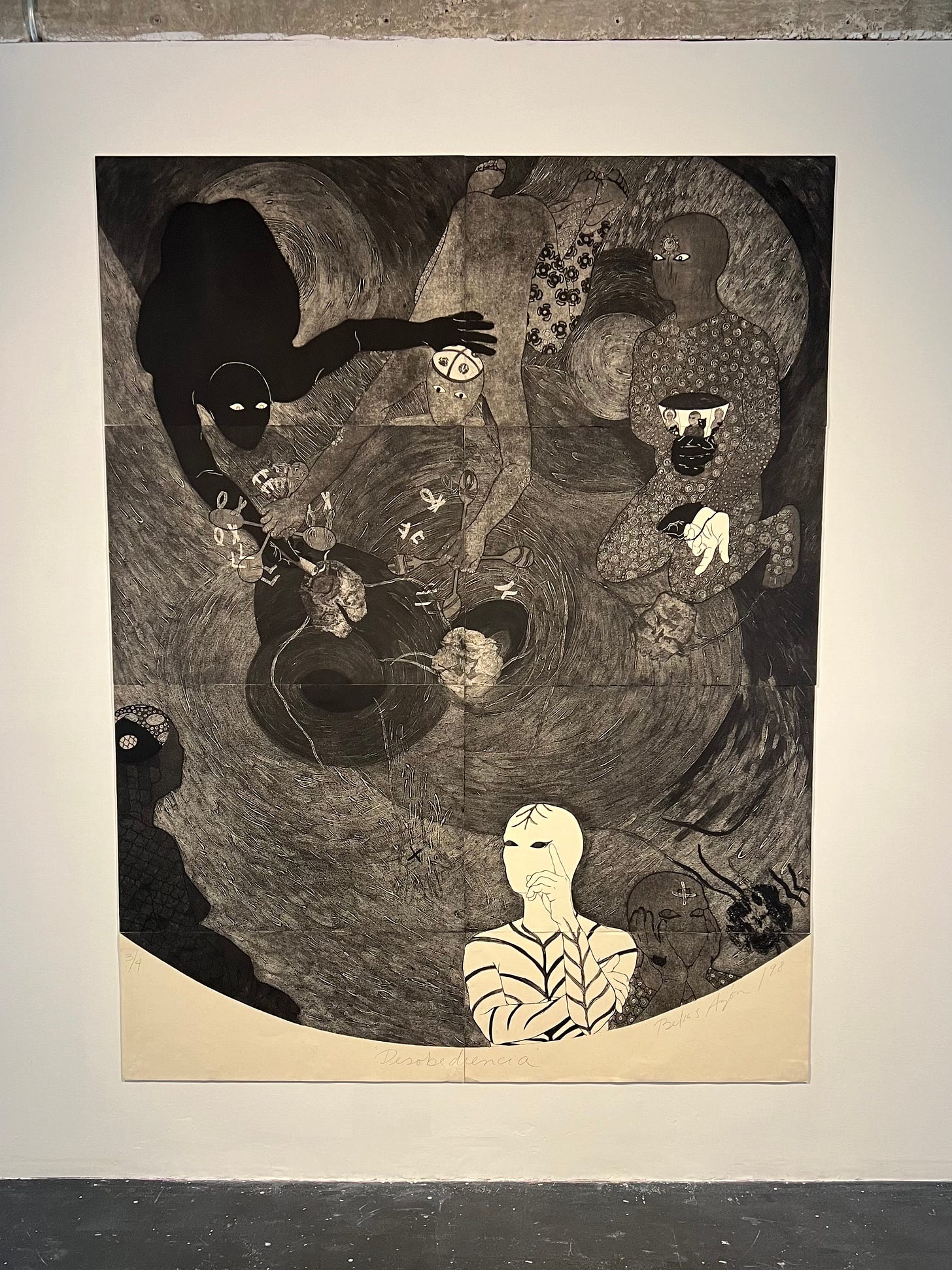

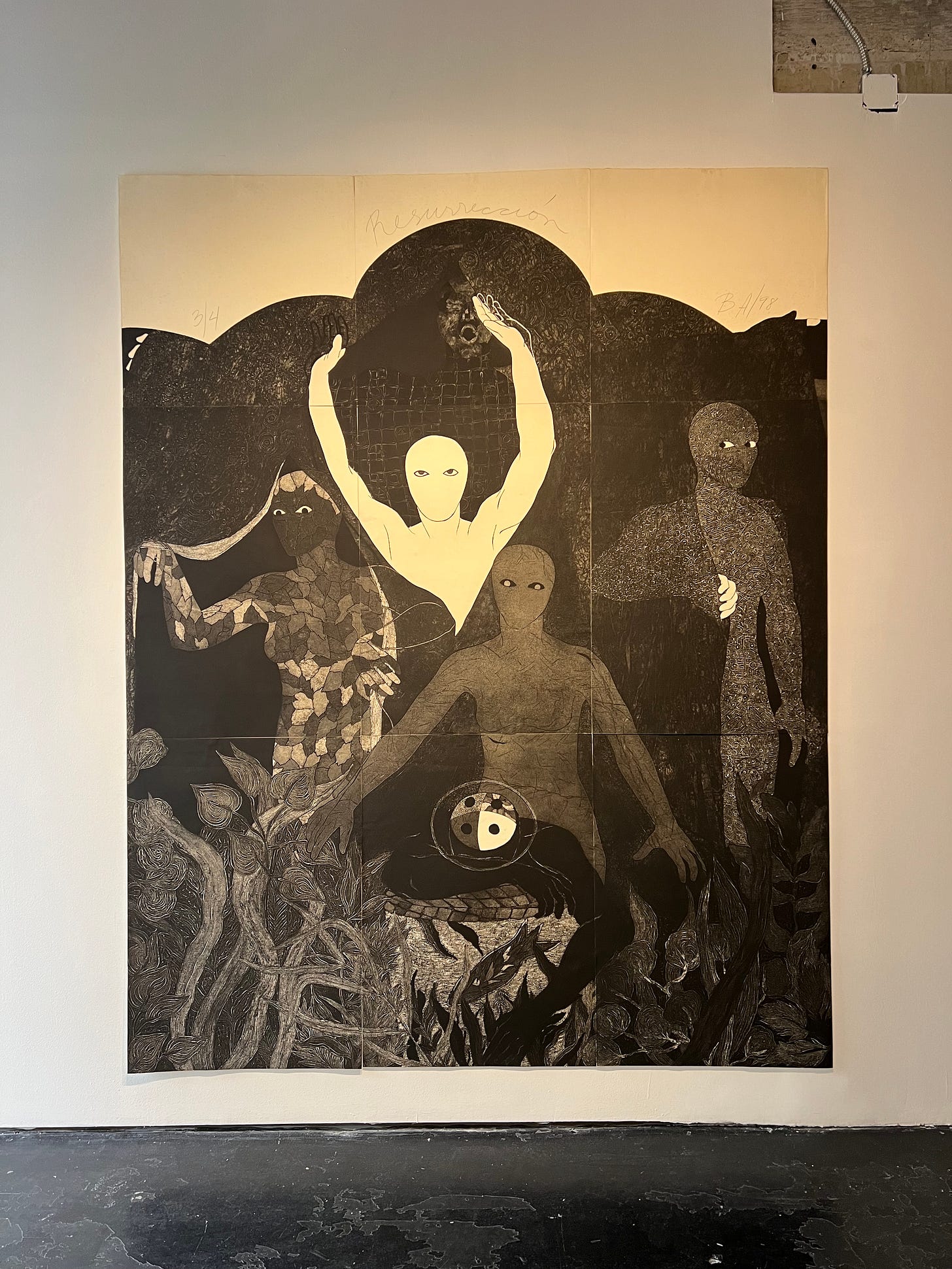

As an artist, and more specifically a printmaker, Ayón’s specialty was collography, a unique type of printmaking in which a plate is made by adhering different objects or materials to a solid backing that is then inked and pressed onto paper. Ayón applied this technique to large-scale prints, predominantly in a grayscale, and depicted mysterious human-like creatures, animals, and symbols. Her inspiration was her interest — and perhaps obsession — with the Abakuá religion, a secret all-male Afro-Cuban religious society. In the David Castillo show, the figure of Sikan—Abakuá’s sole female deity— takes center stage in many of the works.

In Abakuá mythology, Sikan is sacrificed for her sacred voice after she accidentally catches a fish believed to be a reincarnated king. The tribe’s oracle, Nasakó, realizes that Sikan has the sacred fish, and he and his men send two snakes to her to scare her so she drops her water vessel. She does, yet the fish is unable to be saved, so the men believe that perhaps the voice has transferred to Sikan’s skin, sacrificing her to make a drum from her skin, yet the sound fades and they must keep looking.

The story is gruesome and mysterious, but one that resonates with Ayón and appears in her work. Visually, she often incorporates elements of the myth into her collographs, especially Sikan with the fish and surrounded by the snakes. At the same time, Ayón, in a 1993 interview with journalist Ines Anselmi featured in the gallery’s exhibition catalogue, explains that her work is not just a retelling of the myth directly, but rather her own vision into a world she can never experience:

I don’t know if you’re thinking that what I do in my work is simply reproduce the Abakuá myth as is, but actually I don’t do that. In fact, my goal is to synthesize the aesthetic, visual, and poetic details that I find in Abakuá mythology and to add my own vision — which is, of course, simply the vision of an individual observing all this great mythology, which I treat with enormous respect and care. What can be seen in my work is a kind of series of flashes of a sacred memory that I did not live through exactly, but that I always have in my memory because of the research I did.

As spectators, we are of course not privy to the intricacies of the Abakuá society, but we nevertheless feel welcomed into its mysteries and peculiarities. Even more so, the context of Ayón’s work, in its current show, further adds to this experience. The gallery space is on the second floor of a building in the Miami Design District; a small white-walled room with a dark concrete floor and exposed ducts on the ceiling. It’s industrial, yet extremely refined and intimate, which made the works feel even larger than life. I stood in the gallery alone with the work, isolated yet keenly aware that I could feel and experience everything the artist wanted me to see and feel. Removed the bustle of a museum hall, from extraneous noise, lengthy wall-texts and labels, or even the anticipation of another room of art around some corner, David Castillo Gallery acts as a sanctuary where Belkis and her vision of a strange and unusual world come to life.