There is another world inside this one--- no words, can describe it. There is living, but no fear of death; There is spring, but never a turn to Autumn. There are legends and stories coming from the walls and ceilings. Even the rocks and trees recite poetry. from A World Inside This World by the 13th-century Sufi poet Jallakuddin Rumi

This poem opens Lisa Lyons’ essay “The Poetry Garden by Siah Armajani,” in Design Quarterly, No. 160 (1994). I thought it a perfect place to start this piece about the life of Armajani’s Poetry Garden that was created as a small park in west Los Angeles, California, and then transformed into a garden-classroom on the campus of Beloit College in Wisconsin. In both locations, the garden served as a refuge for people to pause their daily routines to reflect on art, nature, and community.

In 1992, the Lannan Foundation commissioned Siah Armajani, a celebrated public artist, to transform the barren industrial plot in front of their new headquarters in Marina del Rey into a garden courtyard. Armajani created the Poetry Garden for the courtyard to serve as a quiet haven for visitors to the foundation’s offices and art gallery, as well as a site for poetry readings and performances. Literature and art were the focus of the foundation’s philanthropy at the time.

Iranian-born American artist Siah Armajani (1939-2020) was uniquely qualified for this project. Armajani possessed a deep interest in literature, using Persian and American literature as inspiration for his art. The Lannan’s Poetry Garden was inspired in part by “Anecdote of the Jar,” a work by the American poet Wallace Stevens (1879-1955) that describes the transformative power of art. A guiding principle for Armajani was to create functional public works. Notable among his public art projects is the Irene Hixon Whitney Bridge, a 1988 pedestrian span which reconnects two Minneapolis parks that had been severed by 16 lanes of freeway. In both this bridge and the Poetry Garden, Armajani replaced urban scars with functional spaces of beauty for the community. Armajani spoke of his artistic purpose in a public discussion, January 1986, “I am interested in the nobility of usefulness. My intention is to build open, available, useful, common, public gathering places. Gathering places that are neighborly.”

On April 2,1992, shortly after the inaugural reception of the Poetry Garden, art critic Christopher Knight wrote a review of the new garden for the LA Times offering immediate praise for the magical space. Knight described garden’s features and layout:

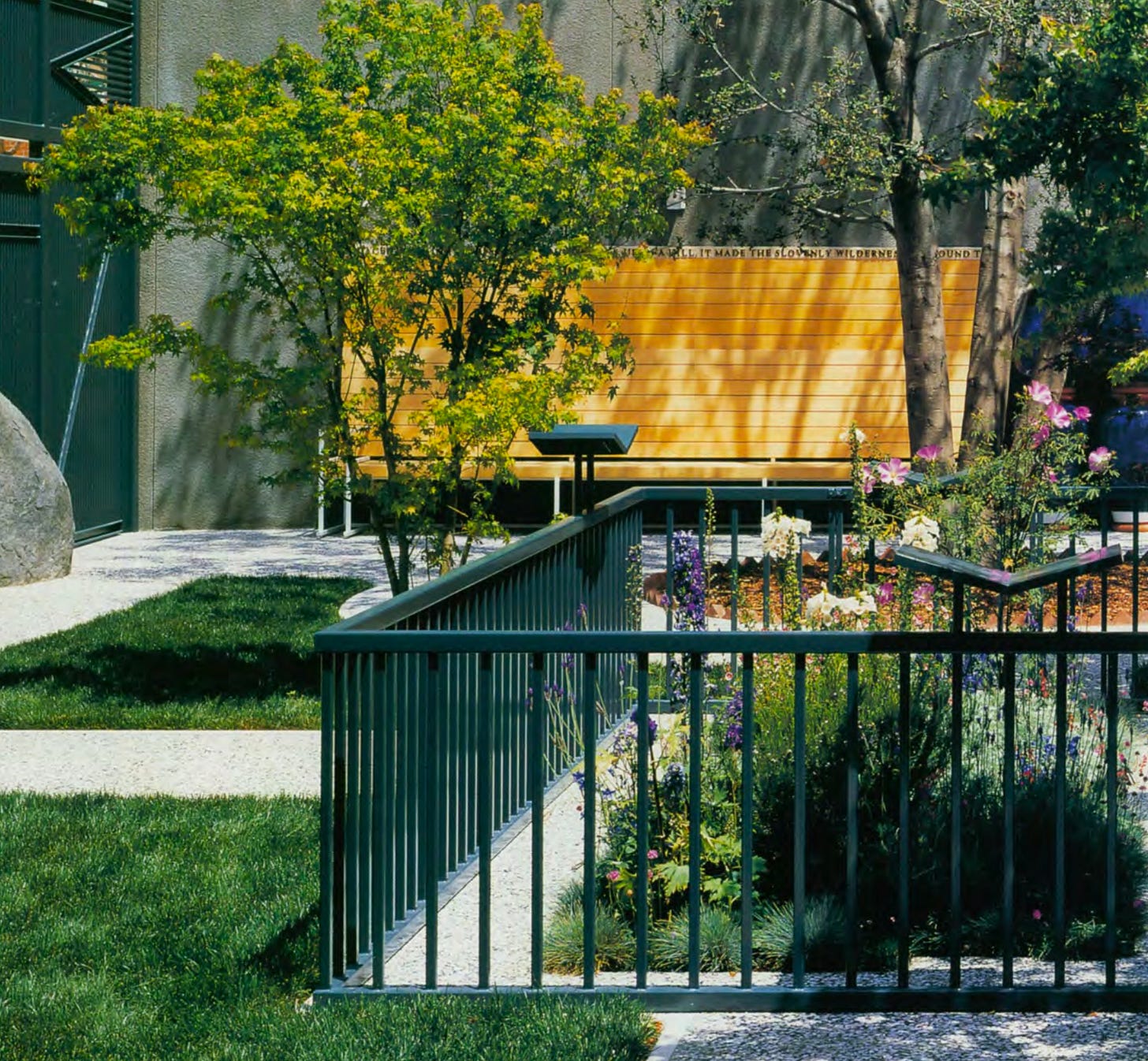

“…modest in scale, enclosed on four sides and opening onto the street through wide gates at one corner, it felt like a public park. High-backed armchairs and benches surrounded the perimeter of the space. At the southeast corner, a break in the perimeter seating is filled by a row of 15 pairs of tall ceramic jars. The vessels are a key to a principal inspiration for the garden: Wallace Stevens’ poem “The Anecdote of the Jar,” whose three stanzas are printed in a single line of ceramic tile around the top of the high-backed seating. A meditation on the uneasy tensions between nature and culture… The small, densely packed flower bed is the heart of the space. Its fence is surmounted by four podiums from which readings can be given. A speaker can stand inside the flower bed and read outward; or, he can stand outside the flower bed and read across it, to an audience seated at the perimeter…”

Within a couple years, Angelenos who worked in buildings in the industrial park adjacent to the Lannan Foundation were frequent visitors to the garden. On June 6, 1994, Ken Moritz, a retired writer for TRW, wrote in the LA Times about the Poetry Garden as his favorite place: “I appreciate this place as a kind of sanctuary, a refuge from the industrial flatland that surrounds it. It’s a nice place to drop in and get a whiff of poetry or just meditate. Each of the four lecterns has a different book on it. Someone in the morning will put out the books. I like the kind of trust of this place. Today I was struck by the Vietnamese poet, and I thought I’d sample a couple of others. I don’t usually read much poetry—this is kind of a chance to get a look at it. In the summer they offer poetry readings followed by a reception. It’s just great.”

To the artworld’s surprise and Angeleno’s dismay, in 1996, the Lannan Foundation created a museum acquisition and gift program to disperse their art collection throughout the United States. This was the result of the foundation’s shift in philanthropic focus to the Indigenous Communities Program to address the urgent needs of rural Native American communities. The foundation headquarters relocated to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1997.

As part of the collection dispersal, the Poetry Garden was a gift from the Lannan Foundation and the artist to Beloit College in 1997. Beloit College is a private liberal arts college in Wisconsin. Founded in 1846, when Wisconsin was still a territory, it is the state's oldest continuously operated college. Two ties to the Midwestern college brought this significant piece of public art to the campus. The VP for enrollment at Beloit College in the 1990s, Alan McIvor, was Armajani’s friend and college classmate, and the college president at the time, Victor E. Ferrall Jr. was a friend of J. Patrick Lannan Jr., president of the Lannan Foundation. What’s more the artist was familiar with the college because three of Armajani’s nieces are Beloit College alumni.

Armajani renamed and redesigned the garden before it was installed in Beloit. Renamed the Beloit Poetry Garden, it maintains the purpose and function of the original garden, serving as a place for gathering and as a sanctuary for quiet reflection. The layout is larger, about four times its original size to accommodate various seating areas for classes, performances, and informal gatherings of students and the community. Typical of Armajani’s public art approach, he responded to the context of the new location—the specific area of the campus and the climate. Situated on the southeast corner of campus, the redesign involved incorporating the old-growth trees, planting small trees to delineate seating areas, and acknowledging the architecture of campus buildings that frame and communicate with the garden. In consideration of the climate, appropriate materials were identified to use for outdoor benches and tables, and plantings were selected to mark the four distinct seasons. Today the garden is a beloved landmark of the campus.

This spring I spent three weeks at Beloit College (my alma mater), working with five students to develop a guide for the public art on campus. It was very early spring, just as the garden was “waking up,” no leaves yet on the trees, and daffodils attempting to bloom, as the garden awaited visitors to sit among flowers and under the shade of the trees. One of the seminar students wrote about the Beloit Poetry Garden. I’ll close with a student’s experience of Armajani’s garden.

April 2024, Evelyn Manchester, Class of 24, wrote of the Beloit Poetry Garden: “As you move into this space, what do you first notice? Is it the open doors, or maybe the different benches scattered throughout? This is Siah Armajani's Beloit Poetry Garden, which was installed in 1998. The latest of three works by Armajani in Beloit, the Beloit Poetry Garden invites people from both the city and college community into a shared space. For Armajani, his art must always be beneficial and useful to the public and this garden is a prime example of how Armajani fuses functionality and art.

The three tables, each ranging in size and location, are often the first functional aspect identified. These tables are frequently used in the warmer months by clubs or classes for meetings. They are positioned throughout the garden, each connected by paths lined with plants. Benches of different sizes are scattered throughout the garden. One cluster of these benches, which are lined up like church pews, faces towards the centerpiece of the garden. A large green metal rectangle sits at the center. With four lecterns positioned along its edges, this portion is faced by the benches arranged as pews in preparation for a poetry reading or similar event. Perhaps the most impactful aspect of the Beloit Poetry Garden is the doors positioned at the south end of the garden along the street. They open towards the campus, as if the garden is inviting the Beloit community into the space. There are many hidden details throughout the garden that can be spotted by walking through the space.”