Free Art Friday: The Vanishing Public Art of Ana Mendieta

Ross Karlan, Director of Art Muse LA and Miami

Though she died almost 40 years ago, 2024 was a year that very much felt like Ana Mendieta was still alive. January 24th marked the death of Ana’s husband, minimalist sculptor Carl Andre, whose declared innocence in her tragic death is highly contested in the art world. Andre’s passing sparked intense fervor among Mendieta’s fans, reviving the sense of anger, betrayal, and conflict associated with her untimely demise. Just a few months later, in May, following the passing of renowned Miami collector Rosa de la Cruz, Mendieta reached an all-time auction record, with her Untitled (Serie mujer de arena / Sandwoman series) selling for over $560,000. Rosa de la Cruz, along with her husband, Carlos, was one of Mendieta’s most prominent and prolific collectors, and the now-closed de la Cruz Collection offered a stunning array of Mendieta’s work on display, at no cost to the public.

As an admirer of Ana Mendieta for many years, I understood the rollercoaster of emotions among her super-fans. I had finished Helen Molesworth’s brilliant podcast Death of an Artist just a few months before Andre’s death, and felt the desire for vengeance, so I quested to pay homage to her incredible work.

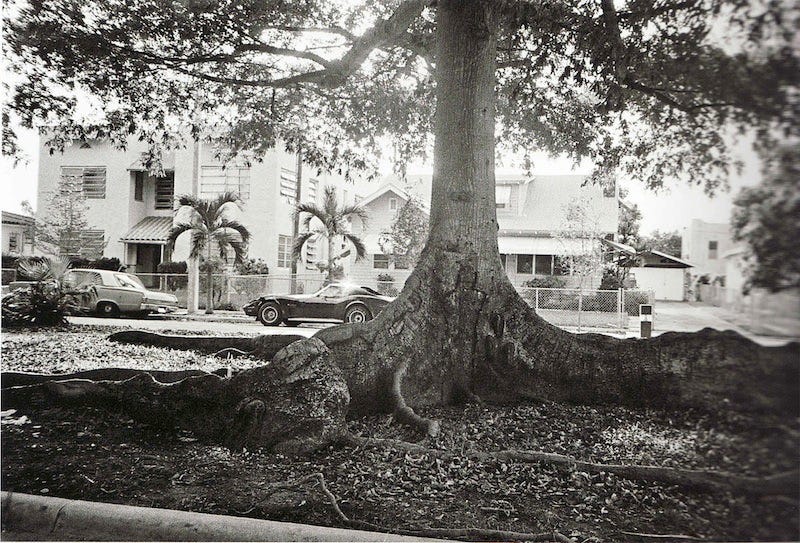

I remembered a story that a local Miami artist and friend had told me that felt almost too strange to be true. Over coffee, he said something along the lines of, “if you’re walking past the Bay of Pigs Memorial in Little Havana, follow the stench of chicken poop and you can’t miss it.” The location was an enormous tree in the median of SW 13th Avenue that had a carving by Mendieta of one of her siluetas, called Ceiba Fetish, from 1981. Why the chicken poop, you may ask? Today, the site is a prominent ritual site for local santeros, practicians of the Afro-Cuban religion Santería, and let’s just say sometimes chickens are traditionally involved in various rituals (though none have been present when I have been to the tree). With or without the chickens, santeros use the space due to Mendieta’s deep inspiration from her country’s mysticism and traditions, acknowledging the mystical qualities of her silueta figure that channeled notions of femininity, fertility, and spirituality.

The work in Little Havana appeared after Mendieta had made a journey back to Cuba in 1981. She lived the majority of her life in exile, landing in Iowa as a child as part of Operation Peter Pan, an organized attempt to airlift Cuban children to the United States shortly after the Cuban Revolution and Castro’s rise to power. On the trip back in 1981, Mendieta created an iconic in situ series of rock carvings in limestone caves outside of Havana, and brought that same energy and spirit with her to Miami for Ceiba Fetish.

While the work is either hardly visible or not there at all — depending on how much you believe it’s there as the viewer — knowing the history of that tree in the middle of a street in Little Havana somehow keeps Mendieta’s intervention alive. It also marks something ephemeral and passing about public art that we don’t think about very often. Sculptures, murals, and other public interventions appear, at least, to have a sense of permanence. Yet Ana Mendieta made sure that her interventions in the natural world could be fleeting and haunting, a specter that you know was there, but has a lasting effect, just like her own life would end up to be.