Free Art Friday: The Lesser-Known Sculptures of Matisse

Chloe Landis, Art Muse Lecturer and Museum Educator

French artist Henri Matisse (1869-1954), is one of the giants of the first half of the twentieth-century art world. He is known for his play with vibrant contrasting colors and expressive brushwork. In his own words, Matisse said his works were “construction by colored surfaces,” a theme that was prevalent throughout his entire career amongst his many periods of work.

But nestled on the edge of UCLA’s campus in the Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden, hangs a diversion from his colorful canvases and, instead, displays his less known medium of sculpture.

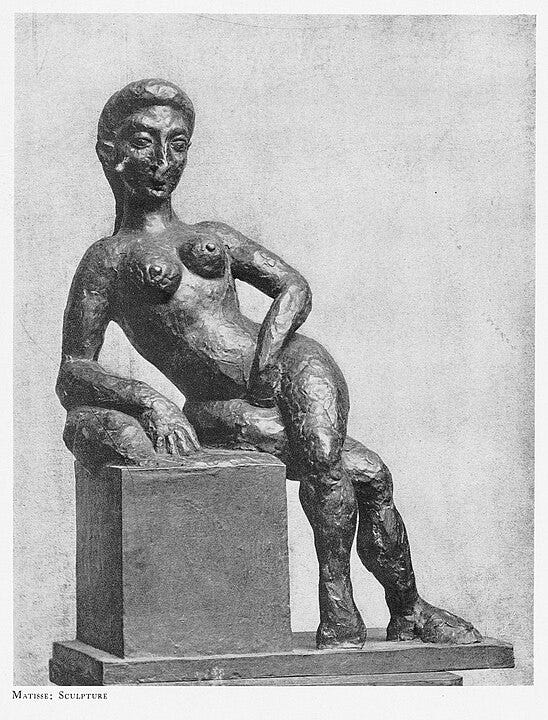

While there are countless paintings and drawings from Matisse, he made only about eighty sculptures, most of which he completed in the first half of his career. Matisse trained at the École des Beaux-Arts under Gustave Moureau, who had a liberal attitude for the time and encouraged Matisse to find more ways for creative expression. So Matisse sought out sculpture, though he had very little formal training. Initially he attempted to study with Auguste Rodin—considered the father of modern sculpture—but Rodin was not impressed. So Matisse worked with one of Rodin’s most successful students, Antoine Bourdelle. Matisse was inspired by both Rodin and Bourdelle’s partially misshapen expressive forms, which translated into his early sculptures, where the surface is rough and definition of body parts to background or stand become fuzzy.

On the Broad Art Center walls at UCLA hang Matisse’s Bas Reliefs I-IV, or Back Relief, which are some of his best known sculptures. Four life-sized bronzes are side by side, each depicting the back of a nude woman with her left arm raised above her head, resting her forehead on her arm, her pose relaxed with her weight shifted to one leg, and her right arm hanging beside her. From left to right, the works become more abstracted. The definition of limbs and muscles disappear, as does the curvature of the body, the breast, and the specificity of gender. The hair knotted at the nape of the neck on the far left unravels until it becomes one long block to match the blockiness of the body and limbs on the far right. On the stereotypical sunny California days, the sun beats down on the bronze and emits a glimmer on the surface, while the shadows of the bodies deepen and shift with the sun.

The Bas Reliefs were made across a period of twenty-one years, from 1909-1930, and though they are equal in size, style, and subject matter, Matisse did not consider these to be a series of works. Rather, each was an evolution from the next as his style evolved over time. Matisse frequently used sculpture as a three-dimensional way to work through problems in his paintings or as inspiration. Because of this, parallels in style between the sculptures and paintings of the same years emerge. The women's relaxed pose is consistent with the languid women Matisse reproduced continuously throughout his career. The bodies in Matisse’s Dance from 1910, for example, share almost the same form as the very first Relief. As the latter two figures in the reliefs begin to blend into the background of the sculpture, so too did Matisse’s paintings start to compress space as foreground and background begin to blur.

Matisse shared that his goal was to find the “essential character of things” and to find and make art of “balance, purity and serenity.” For him, abstraction was a way to find that essence. Something which appears to be so simple required numerous preparatory drawings and extensive labor to achieve the result he wanted. The Bas Reliefs allow us to see Matisse’s progression as an artist, as he sought out in finding the purity that he was trying to capture. Matisse’s move towards abstraction not only demonstrates his shift stylistically, but also shows his commitment to seeking that which is not right before our eyes, but looking deeper and with a different lens at the world.

Take a moment sometime today and find something in front of you and try looking through Matisse’s eyes, breaking it down to simple lines and shapes. As you look carefully, consider what you may not have seen before and what “essential character” may be underneath, waiting to be found.