Echoes in Empire: Victorian England in Ancient Rome — Alma-Tadema & John William Godward

Chris Suzuki, Art Muse Lecturer

At the end of the nineteenth century, the British Empire was the most powerful on earth, wealthy and constantly innovating in technology, science, and the arts. Spreading its reach around the globe, it saw itself as the inheritor of the mantle of Rome and western civilization writ large. The British sought to connect themselves visually and culturally with the best of the ancient empire and to be a model civilization. This desire came through in everything from philosophy to science, but was seen most clearly in the Academic paintings of the age, where Victorians depicted themselves in the great places and events of history. Though many artists would explore these themes, two of the best and most successful were Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema and one of his proteges John William Godward. On view at The Getty Center in Los Angeles are two of their most famous works “Spring” and “Mischief & Repose” respectively. Each is a perfect example of the mix of art and commerce that exemplified the age, along with the high Romanticisation and meticulous detail that the Victorians loved. They are a masterclass in the craft of realistic texture painting and each blends the sensual with the scholarly in a way typical of late Victorian art. Taken together they are a snapshot of the headspace of the age, a manifesto on how the Victorian British wanted to be seen and how they saw themselves.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema was a Dutch artist who came to England in 1869. Inspired by the ancient monuments and art he saw on his honeymoon in Italy, he would go on to be one of the most praised and financially successful artists of the nineteenth century. Best known for his scenes of beautiful women against meticulously rendered marble and Mediterranean skies, his work was actually a mirror of Victorian society showing both the dignity and the decadence of the time. Famous for researching every detail in his paintings so they would be historically accurate, he created historical fantasies connecting Roman and Victorian life. This is perfectly displayed in his masterpiece, “Spring,” completed in 1894 after four years of work.

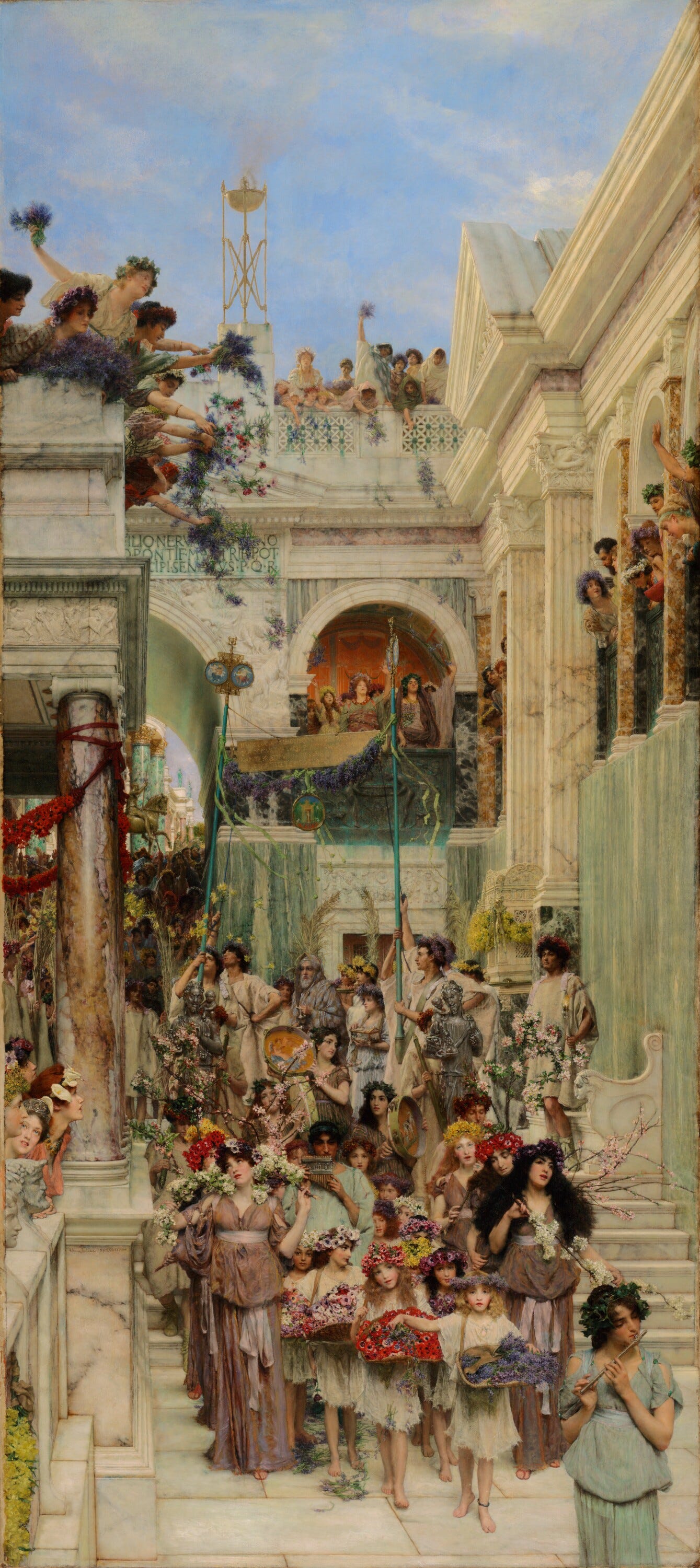

The scene is of an ambiguous flower festival in ancient Rome, where a procession descends a white marble staircase. Children with baskets of highly detailed flowers come first, then musicians playing , then the throngs of revelers exiting from the Forum of Trajan — seen through the arch — all with flower crowns. Surrounding the staircase are a multitude of temple facades and palace balconies all made of different marble and carved, from which more revelers throw flowers on the procession. Among the musicians are two attendants carrying a bronze banner that has a dedication by the real roman poet Catullus, from Latin it translates to,

I dedicate, I consecrate

This grove to thee,

Priapus, whose home and woodlands

Are at Lamsacus,

Thee, among the coastal cities of the Hellespont,

They chiefly worship thee,

Their shores are rich in oysters.

Above this dedication is a balcony where the imperial family can be seen with a room of the palace behind. Sculptures, dedications, and banners fill every corner of the image along with an overabundance of flowers. Tadema also designed the frame which is in the shape of a temple facade with pediment, gilded, with the title of the painting at the top. At the bottom of the frame are lines from Swinbirne’s poem “Dedication” (1869)

In a land of clear colors and stories,

In a region of shadowless hours,

Where earth has a garment of glories

And a murmur of musical flowers

The rest of the poem remains unquoted and speaks of finding amorous pleasure in the springtime. This poem was considered risqué when it was written and it belies Tadema’s connection to the Pre-Raphaelites. Swinburne himself used the dedication seen in the image as inspiration for two of his own poems. The poem’s hidden sexuality behind the innocent image of spring flowers is central both to the painting and to Tedamas work in general. Priapus himself was a god of gardens, hence his placement here, but also his erect phallus, a symbol of fecundity, is referenced with the oysters — an aphrodisiac. These quotes, along with the carvings on the buildings being mostly of nude amorous couples, speak to the forbidden desires that Victorian society hid behind images of purity and innocence. Such topics could be broached in art as long as they remained in the classical period and thus the connection between ancient and modern empires was perfect.

The Victorian public also enjoyed the titillation hidden under history that much of Tademas' work provided. The statues, instruments, clothing, and architectural elements are all exact replicas of ancient art either from the artist's own collection or studied at the British Museum but thrown together into an architectural fantasy known as a capriccio. This speaks to the dual Victorian obsessions with perfectly cataloging the past while also Romanticizing it beyond recognition, myth and history coming together for effect. Tadema’s ability to do this so well was what won over the public, his scholarly rigor and technical skill was what impressed the Academic painters, and his sense of beauty and composition drew the Aesthetic artists. He also sought to connect England to Rome by keeping the festival ambiguous. At that time social reformers were trying to revive old English folk traditions like children going out to pick spring flowers on the first of May. In this painting Tadema is connecting this tradition with the ancient Roman celebration of flowers called the Floriana. By doing this Tadema is connecting English tradition with the authority and dignity of Rome and emphasizing Britain's history as a Roman province; giving a pseudo source for the tradition. All the flowers shown grow mostly in England and the faces in the crowd were modeled on the artist's own friends and family to give them a modern look. He wanted Victorians to see themselves in ancient Rome and for it to come alive through his work, thus making their own historical moment feel important and mythic by proxy. Tadema's beauty and escapism allowed Victorian London to justify their culture and their expanding empire as the “New Rome”.

Tadema would inspire many artists in the generation that came after him, none more so than John Willam Godward. Godward was born in England in 1861 and was one of the last artists of the Neoclassical era, learning everything he could under Tadema. He too would become famous for women in classical dress against landscapes and rich textures from the ancient world. The art-buying public of Godwards time knew the symbolism used in ancient Rome and he utilized this knowledge to deepen the meaning of his work and connect it to modern times.

A perfect example of his style is the painting entitled “Mischief and Repose'' completed in 1895, just a year after “Spring”. In this work two young women lounge in a marble lined room, one is lying on a tiger skin on a marble bench clothed lightly in a transparent blue chiton, while the other sits on a black bear rug. She wears a peacock green see through chiton and is annoying the other with a dress pin, there is another pin on the bear rug and a maroon curtain in the background. This work is a triumph in texture painting and a real credit to Godwards mentor Tadema; each marble is distinct and layered, the cloth looks light and soft, each surface perfectly executed with a neoclassicist's precision. The women each represent one of the ideas of the title, connecting the work with the symbolist painters who sought only beauty and to convey ideas and dreams rather than life. Thus the work is a neoclassical composition of a symbolist subject, bringing together the two current most popular styles in painting. The work is also another example of using a classical theme as an excuse to look on the seminude female form common in Academic art of the later half of the nineteenth century and creating another work that hides a sexuality beneath the veneer of innocence. The figure's poses remind one more of courtesans of the time than ancient maidens, allowing the viewer to connect past and present. Yet the girls stand apart from the viewer in their luxury, untouchable as women often were seen in Victorian art. This was a work of skill and beauty from an empire at its height seeking to aggrandize itself with all the trappings of antiquity.

The end of the nineteenth century was the height of Imperial Britain and it sought to justify and display its power through the trappings and especially the art of ancient Rome. This desire was furnished by painters such as Lawrence Alma-Tadema and John William Godward who combined the competing trends of the time to create financially successful art that spoke both to the past and the present. Each was a master of technical craft, especially marble, serving the Victorian love of detail and richness, and each hid a level of sexuality beneath the images of purity as a comment on the culture of his time. Both would be widely praised and awarded in their lifetimes, but suffer with the rise in modernism. Yet their beautiful paintings remain as time capsules to their era and the beliefs and aesthetics that built them.