Continuity and Multiplicity: Roman Blending in the Mummy of Herakleides

Chris Suzuki, Art Muse Lecturer

Popular culture would have us see the Romans as ignorant to the cultures they conquered; and Academia would have us see Roman Egypt as the pitiful ending to a mighty history, yet witnesses and objects from that time tell a very different story. Portrait mummies such as Herakleides, currently on view at the Getty Villa, are unique to Greco-Roman era Egypt and speak to a multiethnic, multi-faith people, connected by trade to the wider Roman world, yet still deeply tied to and understanding of their thousands of years of religious history. The complicated Egyptian conception of the soul and its mirroring of the myth of Osiris, first sketched out in the Old Kingdom ( circa 2700-2200 BCE), is clearly outlined in the imagery painted on the mummy. Yet it is made of many materials unavailable before the Roman Empire and in the place of a golden mask is a Roman style realistic portrait. Roman holy colors are used to speak of Egyptian resurrection and Roman fashions altered to fit ancient Egyptian symbolism. Rather than showing ignorance or cultural decline, these mummies show a deep understanding of the Egyptian past adapting to fit a new Roman world. Instead of an ignoble end, Roman era Egypt shows the final flowering of ancient thought and the coming together of the best of its artists traditions, the Getty mummy being a perfect artistic expression.

Herakleides was living in Roman Egypt sometime in the second century C.E., a time when the country was made up of people from all over the Mediterranean, with many having names in both Greek (language of the Eastern Roman Empire) and Egyptian. They shared a mixed heritage, culture, and art that shows up in the mummy which bears a Greco-Roman style portrait for the face, but traditional Egyptian art on the body. Though apparently two separate artistic traditions, the multicultural milieu of the artists allowed them to subtly weave the symbolic imagery of both Roman and Egyptian culture together into a whole, one that spoke to the beliefs and identity of their clientele as well as the multifaceted way they viewed the world.

Yet to understand the imagery depicted on Herakleides’ mummy one must first understand the ancient Egyptian concept of the afterlife and its connection to the god Osiris. In myth, Osiris was the first divine pharaoh of Egypt who, killed by his jealous brother Set, was resurrected after being turned into the first mummy, by the magic of his wife Isis. They conceived a child, Horus, and Osiris went to rule the world of the dead, standing as the hope of eternal life for all Egyptians. The traditional Egyptian imagery painted on the mummy comes from the New Kingdom (1540 B.C.E - 1069 B.C.E.) and is a kind of sparknotes hieroglyphics for the myth of Osiris, acting as a spell for the resurrection of the deceased. That this imagery went back so far before Herakleides era yet maintained its meaning and use shows the understanding the Roman Egyptian artists had of their own religious history. These images are distillations of the spells found in the Book of the Dead, and though they vary somewhat across different mummies they show a sanctioned set of images the artists could choose from.

Starting right below the head of the mummy on either shoulder are Wadjet eyes, symbols for the eyes of Horus, which are the Sun and Moon and shaped like the eyes of a falcon, the Horus’ animal. This speaks to the multiplicity inherent in Egyptian religion, here Horus is standing in for the deceased, the Sun eye is Ra and the Moon eye is Osiris, Ra during the day and Osiria at night, but ultimately one in Horus. The hope is that the deceased will be recognized as these gods through the spells provided and become divine.

This conception of the gods is just one of many the Egyptians had, with forms of gods existing in every possible combination depending on the power or emanation needed. The more options for blessings the better your chances and the less likely to offend some deity by omission. Below the Wadjet are two falcons facing each other, wearing crowns of Upper Egypt and between them a Sun Disk with horns and ostrich feathers. The falcons are once again Horus, and the crown of upper Egypt goes back to before dynastic times as a symbol of kingship, but by the time of the Romans had become a symbol for the goddess Isis. The image in the middle is also a symbol for Isis and thus the Falcons here are Horus specifically as the son of Isis. The Goddess had grown from one of magic, motherhood, and kingship in the Old Kingdom to include the sky and the role of Universal Mother by the Roman period with her cult spreading all over the empire. The second century was the peak of Isis veneration so her imagery here makes sense. The nudity of Herakleides in his portrait was also a common sign of having been initiated into the cult of Isis.

Below the falcons is the image of a winged goddess holding feathers with another feather above her, atop a sun disk. Altars and offering bowls are beneath and on either side of the goddess. The imagery here is intentionally vague; the goddess could be Nut (the sky), Isis or her sister Nephtys or possibly Maat (cosmic order/ balance/ harmony). The feathers are Maat's symbol, Nut gave birth to the Sun each day so the resurrection imagery is there and both Isis and Nephthys are shown with wings with which they embraced the dead. It could be any of these goddesses or just an illusion to all four in hopes they might aid the deceased towards their resurrection, hence the offerings.

Below the goddess is the image of an Ibis on a platform with a sun disk and ceremonial fan. Ibis birds were symbols of Thoth, god of writing, medicine, wisdom, and the moon. His inclusion here may have several meanings, Thoth was a judge of the dead and this painting may hope to appease him. When the mummy was x-rayed in 2002 it was found that the mummy of an Ibis bird was interred alongside Herakleides directly beneath this image. This was the first discovery of an animal mummy inside a human one, although a few others from the era, all with animals symbolic to Thoth, have now been found. Animal mummies were common offerings in Roman Egypt, although the bird's inclusion could also symbolize that Herakleides was a scribe. In Greco-Roman thought all the different gods they encountered were just versions of their own with different names. Thoth was seen as a form of Hermes, the god who escorted souls to the underworld, so there may be even more cultural blending going on with this image.

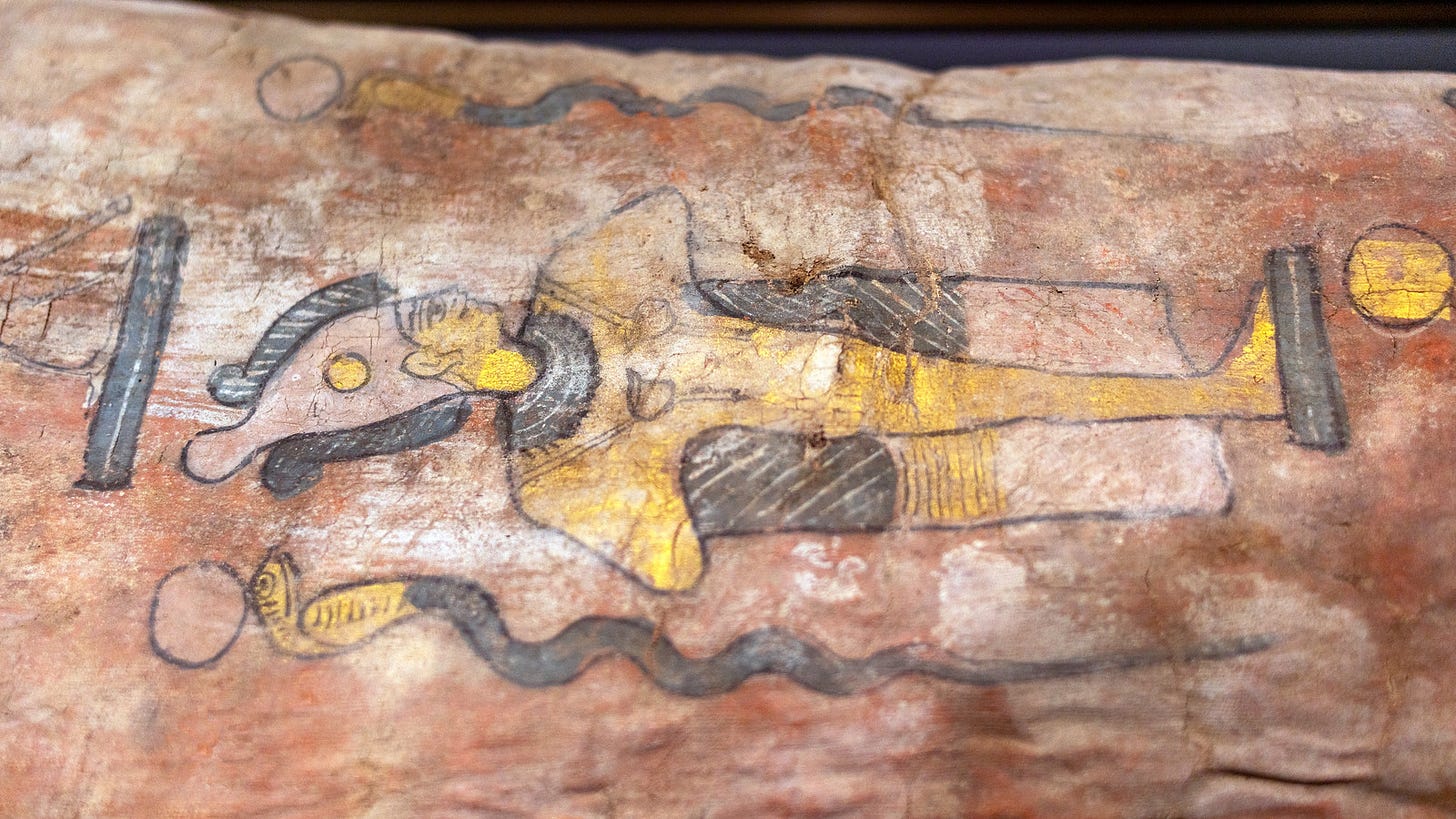

Beneath the ibis are two rearing cobras with Sun disks and between them is the god Osiris in mummy form, wearing the crown of Ra to show their syncretization. The god holds shoulder straps, symbols of high rank in Roman society, and the two cobras are there as signs of protection and the Sun. The blending of cultural symbols of authority shows an understanding of the symbolic language of both Rome and Egypt. Osiris is here as both ruler of the dead and as hope for Herakleides’ afterlife, the young man has now also mummified and hopes to be resurrected like his god. The final register on the mummy is an image of a falcon, Sun disk above his head and a feather in each claw. This is either the avian form of the syncretised Ra/Horus or another funerary deity Soker- Re, god of the necropolis. In either case it is symbolic of the rising of the soul from death into the sky like a bird to the Sun. At the base are paintings of feet, complete with illustrations of gold toe coverings like the pharaohs had been buried with. Gold appears here, as on the images of the gods, and behind Herakleides head because the Egyptians believed the flesh of the gods was made of gold.

When one died the Egyptians believed the soul split into two parts, one stayed with the body and was called the Ba, or soul of mobility, the other took the form of a bird with a human head and was called Ka, or enlivening personality. The Ka could leave the tomb by day and eat the offerings left for the departed, which it used to nourish the Ba when it returned to the mummy at night.. If one performed the correct spells before the gods and passed their many tests, as prescribed in the Book of the Dead, one's soul could then be transformed into a deity or Akh, who then dwelt among the gods forever. Mummification and mummy masks or portraits existed so both the Ka and the gods could recognize the deceased and thus their personality for all time. When the Greco-Romans arrived they applied their tradition of realistic painting to this ancient Egyptian belief creating a new form, the portrait mummy, that combined both cultures. These images resembled the deceased (they had to recognize themselves after all) but not as they were, more as they ideally could be. This was how they wished to be remembered and how they wished to be resurrected in the afterlife. So children who died young were depicted as adults, many portraits depict elaborate jewelry the dead never could have afforded in life and many women wear purple tunics, the most expensive color money could buy. Rome also brought its reach to the materials used on the mummies; Herakleides has a wooden board to support his back made from imported lime wood and the red lead on his mummy would have come from Spain. Red lead was sacred in Roman rituals and used to anoint statues or honor generals in a triumph; using it here further entwined the symbols of the holy of the two cultures. Red lead was one of the first artificial pigments invented and the most valued by Rome, the embalmers included it in mummies additionally as an insecticide. Herakleides portrait itself was made with a mix of beeswax, egg, and pigment in a Roman technique known as wax-tempera. In this process the pigment was pressed into the wax which was blended with egg and oils to slow drying. Herakleides also wears a golden laurel wreath on his head, this was a symbol of victory in the Greco-Roman world, and here it also may refer to the crown of golden light, placed on the head of the deceased, when they reached godhood and the throne of Osiris.

The mummy of Herakleides is a perfect representation of both Egyptian religion in the Roman Age and the larger Roman world. The art cleverly blends references to both cultures in a way that supports their many meanings, and the imagery used shows that even at this late date the Egyptians had a deep understanding of their religious history and concepts. The gods depicted with their many combinations and forms speak to a multiplicity of truth and an acceptance of variance that we often lack today and is desperately needed if we are to face the difficulties of our age. Herakleides sits at the pinnacle of three thousand years of cultural evolution, a symbol of the skills of that age and their hopes for eternity. He looks out at us as a witness to the past and a hope for the future.