I first heard about TERN Gallery in Nassau, Bahamas, at Untitled Art Fair last December in Miami Beach, and it did not disappoint. Between the stunning grayscale paintings of Drew Weech and the eclectic installations of Blue Curry, I was thrilled to know and see first-hand how The Bahamas was making waves in the art world.

Fast forward six months, as I continue to keep up with the gallery’s social media presence and follow the exciting work TERN is doing less than 200 miles over the ocean from where I live. The gallery’s most recent show is titled Balancing Act, a two-person exhibition featuring Drew Weech and fellow Bahamian Jodi Minnis. Through the power of social media and 21st-century technology, I attended an Instagram Live curator walkthrough of the show. I got a deeper understanding of Minnis’ powerful work, followed by some conversation with her.

Jodi Minnis was born in Nassau in 1995 and is an award-winning multimedia artist whose work has been shown worldwide. Her work predominantly deals with questions of gender, race, and cultural identity, scrutinizing, as she says, “the traditional representations and tropes around Black, specifically Bahamian, women.” In many ways, Minnis’ artistic practice is a reclamation of what she describes as the “totality of Black Caribbean womanhood.”

Part of what makes Minnis’ process of reclamation of Black Caribbean womanhood is how she straddles concepts of pop culture and cultural iconography with visual simplicity and exceptional technical execution. Her drawing “Side Eye,” for instance, is one such example of a reclamation of the racist “mammy” trope of the Jim Crow era, or the Bahama Mama figure that appears in tourist shops as salt-and-pepper shakers in The Bahamas. The subtle side-eye glance of the figurine subverts the viewer’s expectations and gives the otherwise inanimate object agency— even sass and sarcasm—breaking it from its cultural bounds.

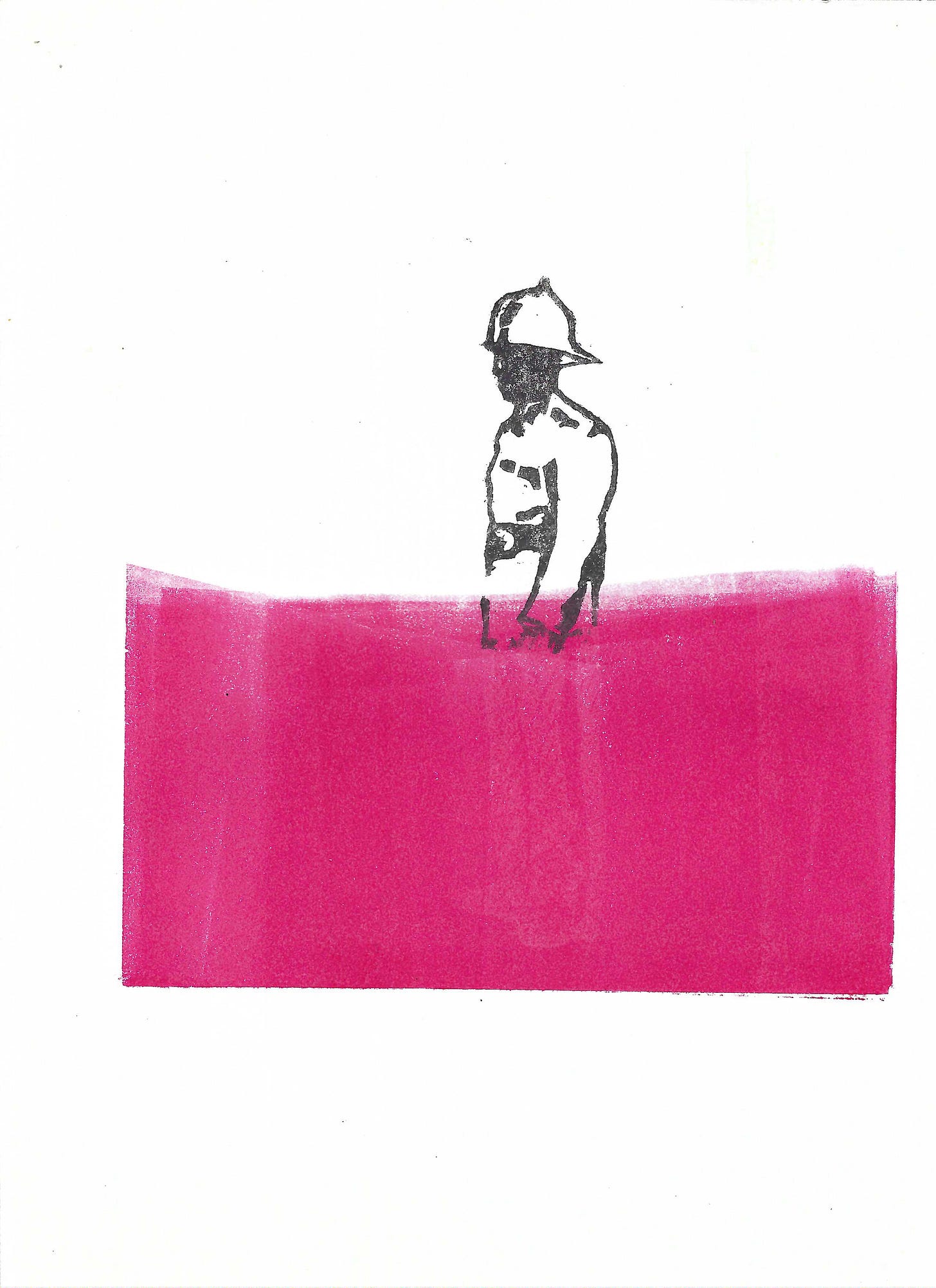

The Bahama Mama figure appears throughout Minnis’ work, often alongside or in conversation with the figure of the Bahamian policeman, another cultural motif found as a souvenir for tourists but also a reminder of The Bahamas’ British colonial past. Minnis ditches the nostalgic and commercial aspects of this rocky history in her prints, such as “Police in Red Sea” (2019), where the policeman vanishes into the red wave of the lower half of the piece. This print is so simple yet powerful due to some striking details that show Minnis’ keen eye in her process of wood-cut block printing. I am particularly drawn to the detail of the policeman’s legs which appear as ghostly white specters in the field of deep red ink. This detail shows that Minnis doesn’t just obscure the policeman by covering him with layers of color but instead gives a more active impression that reflects the title of the piece; that the policeman is drowning in something more fluid and transparent, like the sea.

As I watched the Instagram Live walkthrough of the exhibition, I also was struck by Minnis’ third common motif in her work: the Morton Salt girl logo. As I watched the walkthrough, I learned that parts of The Bahamas, notably Inagua Island, have large areas of salt lakes that, at one point, Morton Salt had purchased to farm salt that was processed back in the United States and then later sold again in The Bahamas. Minnis reflects on this exploitation of the island’s resources and yet another layer of colonialism imposed on the island nation at various points in her work. Her collage, “The Salt Fell On My Head” (2023), is perhaps the perfect example. The Morton Salt girl is supported on a pedestal of native figures and resting on a base of palm fronds. It’s the quintessential culture clash of native identity and corporate capitalism that runs deep in the Bahamian salt industry, something that was new to me as I learned more about the exhibition.

“The Salt Fell On My Head” is also paired with two other collage works, “Two Truths and a Lie” and “All of This Is On My Back,” both also from 2023. As a group, the images reflect Minnis’ reclamation of pictures in a book she found in New York of depictions of the Caribbean that portrayed the region in overly simplistic and prejudiced terms of tourism. Little cues, like serving the old-fashioned cruise liner on a tray like a waiter, or the Bahama Mama peeking her head over the palm fronds, all show Minnis’ critiques, commentaries, and capacity to play with disparate cultural images. Visually, it is also striking to see how Minnis uses her media—notably block prints and collages—to juxtapose these motifs and ideas in different vertical registers. Minnis is constantly aware of cultural hierarchies and stratifications and uses the vertical nature of her works to highlight who is culturally on top or bottom in different contexts.

In addition to being an artist, Jodi Minnis also self-identifies as a “cultural worker.” It’s an apt description, especially to me as an outsider, because of just how much knowledge she puts into her art. Each piece has layers of cultural significance concerning her own cultural identity and her country’s, and I found myself learning so much about each of them. Between her aesthetics, techniques, and brilliant ideas behind her work, it is clear that Jodi Minnis is a force to be reckoned with in the contemporary Caribbean art scene, and no one should be shying away from The Bahamas’ art offerings.

“Balancing Act” is on view until July 1st in Nassau, but more information can be found on the gallery’s website or on Instagram @terngallery.

Follow Jodi Minnis on Instagram: @jodiminnis.

Fabulous read! Thank you for this introduction to such a thoughtful artist.