Wanting to share my knowledge of Aboriginal art after teaching in Australia for many years, I have frequently given lectures on this subject for American audiences (including for Art Muse!). I am often asked where people might see examples in the States of what the Australian art critic Robert Hughes has called “the last great modern art movement.” I have been hard pressed to find exemplary collections beyond very few works in museums such as the Met in New York. So it was with excitement and astonishment that I discovered, while browsing through Facebook, that the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno currently has an exhibition of authentic Aboriginal paintings from its own collection. Only three hours away from my home in Chico, CA, I ventured up to this city known for its casinos to find out how such stellar examples of indigenous art ended up in a relatively small museum on the edge of the Nevada deserts.

Founded in 1931 by local landscape painters, the Museum is now the only American Alliance of Museums accredited museum in the state of Nevada. Its striking building, designed by Will Bruder and opened in 2003, reflects the Museum’s commitment to its geographical region, “a visual metaphor for the institution’s scholarly focus on art and the environment,” as its website states. Its acquisition aims, then, mirror this idea, with a focus on collecting areas related to human interaction with landscape. As its collection statement reads, “In 2012 the Museum defined the Greater West as a ‘super region,’ which broadens conventional definitions of the area by expanding the scope of the collection’s geographic emphasis to encompass the space generally bounded by Alaska to Patagonia and Australia to the U.S. Intermountain West. This is a geography of frontiers characterized by large expanses of open land, enormous natural resources, diverse Indigenous peoples, and colonization—and the conflicts that inevitably arise when all four of these factors exist in the same place at the same time.” Given such an ambitious and far-reaching agenda, it is understandable and appropriate that the Museum would welcome the recent gift of Aboriginal artworks from the collections of Seattle collectors Margaret Levi and Robert Kaplan, and Dennis and Debra Scholl. Works in their collections have also been exhibited at the Seattle Museum of Art.

The exhibition’s title, "We Were Lost in Our Country", refers to a video (2019), purchased by the Museum and receiving its American premier here. The video, produced by Vietnamese-American Tuan Andrew Nguyen, recounts the poignant story of a group of Great Sandy Desert communities painting an enormous canvas, Ngurrara Canvas II, to present in a Canberra court as substantiation of their native title claim. The themes of displacement, colonization, a sense of place, and the power of art are at the heart of the film.

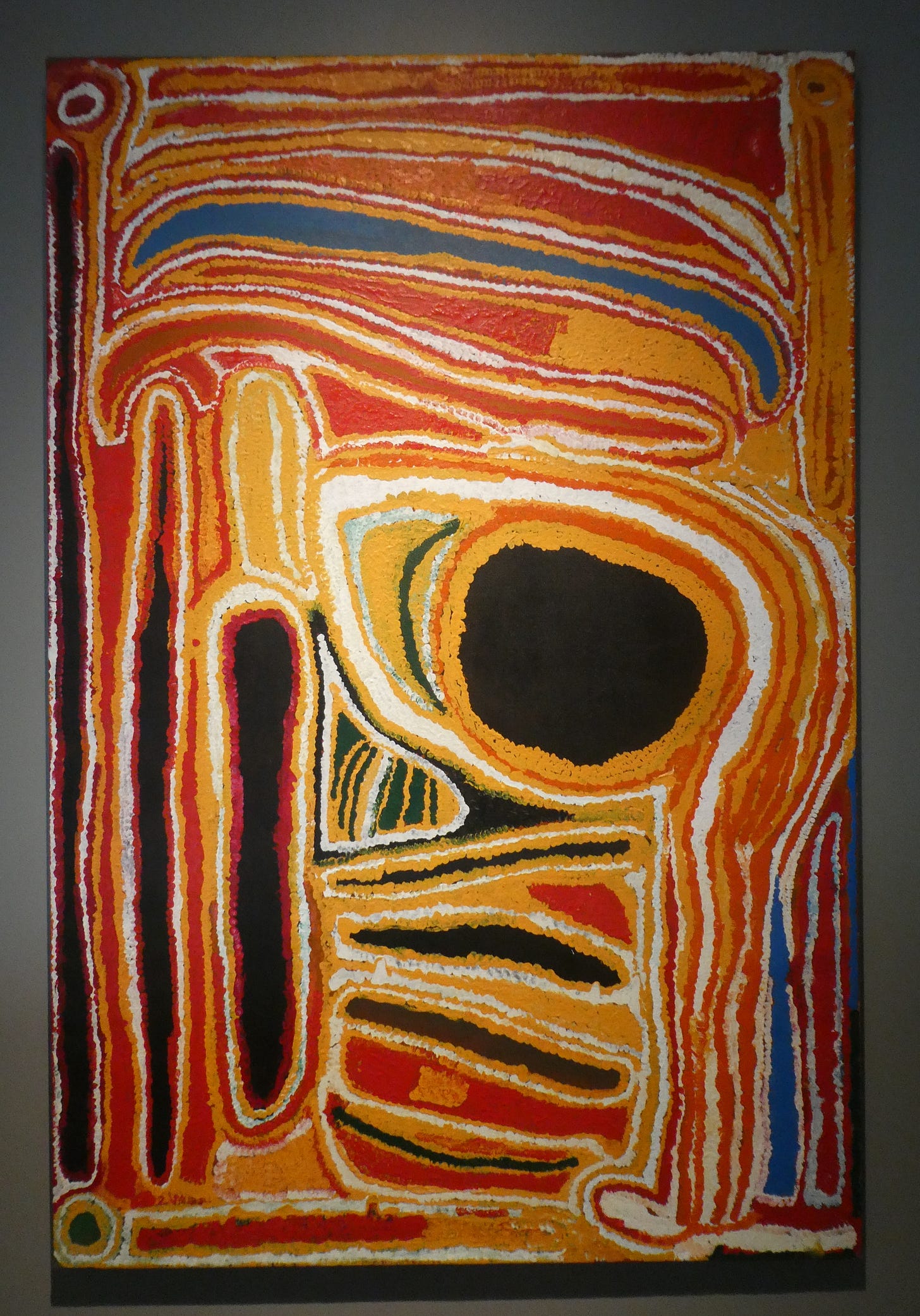

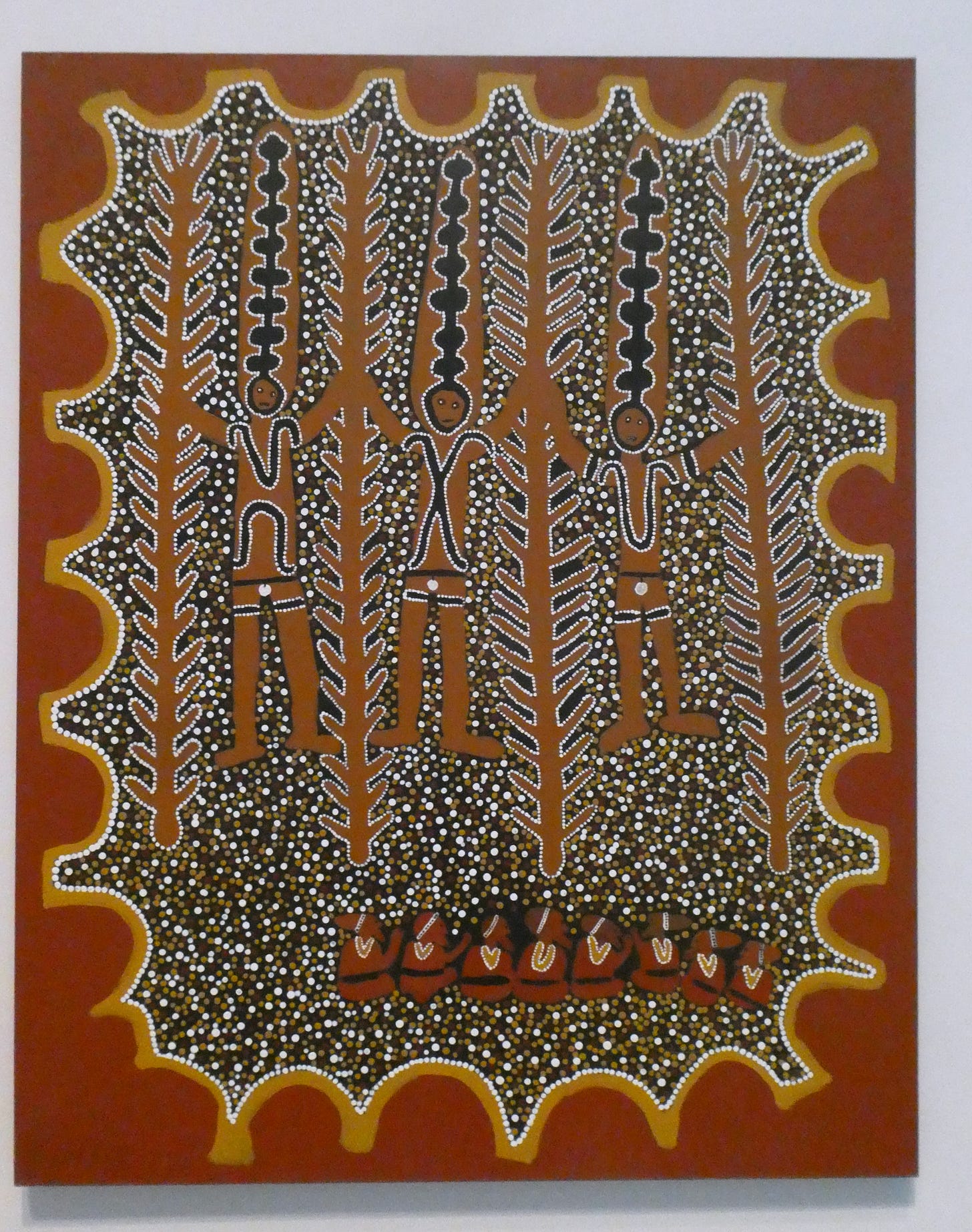

In connection with this screening, senior curator of contemporary art Apsara DiQuinzio has mounted an impressive display of 30 artworks from the Museum’s collection, many of them by the same artists who worked on the Ngurrara canvas. These artworks originated in the Balgo region of the Kimberleys in Western Australia, a remote desert community centered on a German missionary settlement that brought together disparate Aboriginal groups as early as the 1930s. Inspired by the example of the Central Desert artists in Papunya in the 1970s, several members of these various Aboriginal entities at Balgo formed in the 1980s the Warlayirti Arts Center, to support artists depicting on canvas the stories of their land and their Tjukurpa, their Dreaming.

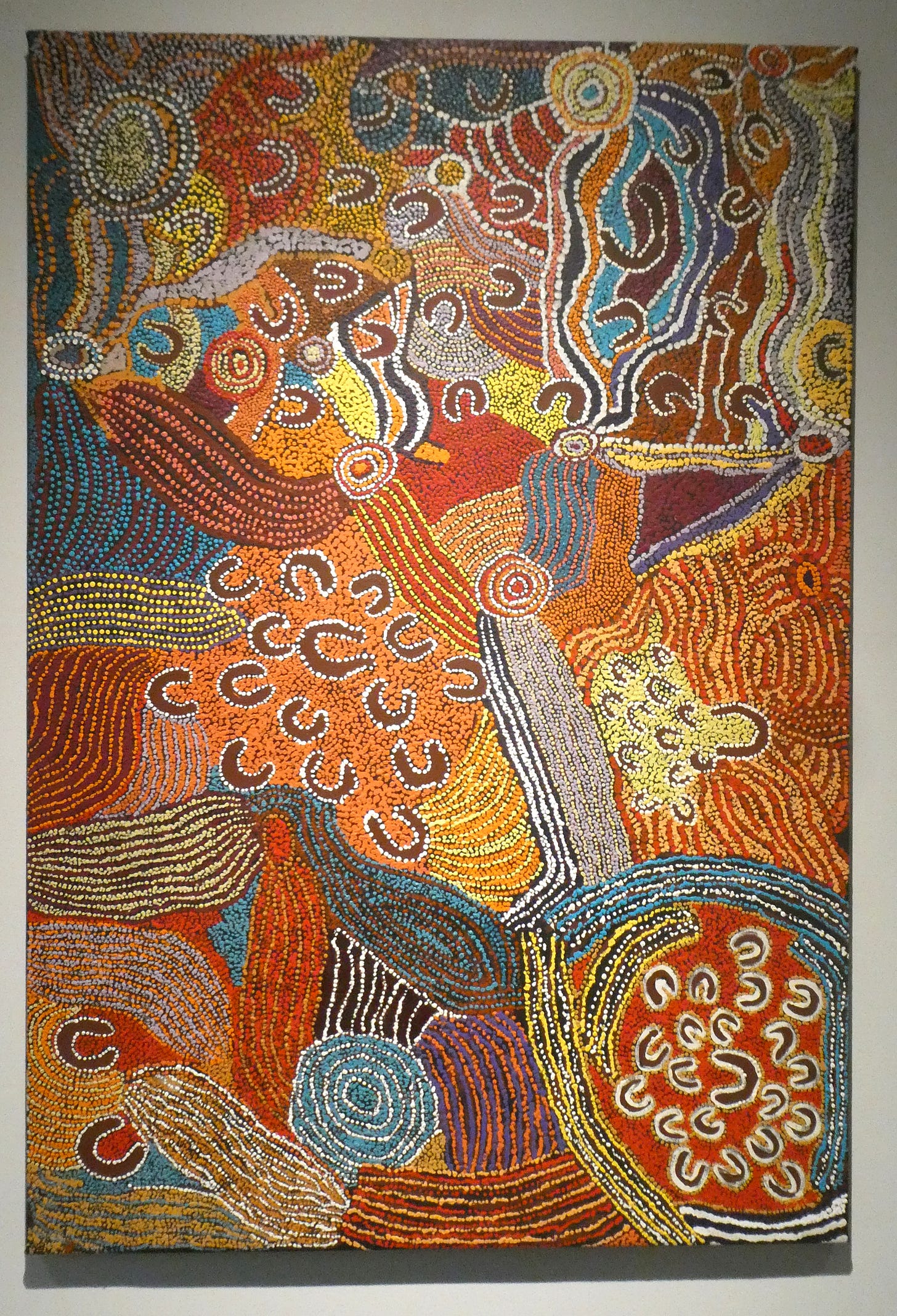

The results of these efforts are some of the most vibrant, colorful, and striking Aboriginal images I have seen. What is most impressive about the exhibition is the care taken in producing informative wall labels to accompany these diverse depictions of the artists’ sense of place and connection to Country and individual Dreamings—the most important themes of all Aboriginal painting. From the earliest painting here—Jarinyanu David Downs’ Yapurnu (1987)—to the later works of the female artists Imelda (Yukenbarri) Gugaman and Elizabeth Nyumi Nungurrayi, each piece is accompanied by comprehensive labels describing what the painting represents to its creators. Several pieces are examples of the collaboration of several artists, depicting their shared conception of their home. The variations in style are also striking, displaying the originality of Aboriginal creativity.

As an example of these commendable descriptions, I include here the wall label for Eubena Nampitjin’s glorious painting of her homeland, Near Jupiter Well (1995):

Nampitjin was among the first and most well-known of the Balgo artists, establishing a signature vibrant style that later came to define Balgo art. She was born at Tjinjadpa, west of Jupiter Well, and was taught to be a healer by her mother. She moved to the Catholic mission in Balgo Hills (Wirrimanu) in 1962 with her family as a result of severe drought. When she was young, she worked with Father Anthony Rex Peile to compile the Kukatja dictionary. . . Nampitjin’s first artworks on canvas were made with a stick. She started painting in the late 1980s using a brush, and her works became highly sophisticated expressions of Dreaming (creation) stories. Significant themes for her were Kinyu (a spirit dog), Tjukurra (rock holes), Tjumu (water holes along the Canning Stock Route), and Marlu (kangaroo), among others. Jupiter Well is along the Canning Stock Route—a cattle trail made by Western missionaries that stretches over a thousand miles across the Great Sandy Desert. Nampitjin’s paintings are in many leading museums in Australia, including the National Gallery in Canberra.

Other labels delineate the near-hieroglyphic symbols of the paintings, which are often described as recognizable maps of the artist’s land. That the curator and the Museum have included such well-informed descriptive panels is rare for exhibitions of Aboriginal art, and are greatly appreciated by anyone trying to understand the representational aspects of this indigenous art. These images are not just colorful abstractions, but represent, as the Aborigines say, COUNTRY—their place, their Dreaming, their land.

What is especially exciting to realize is that the Nevada Museum of Art plans to mount more indigenous art exhibitions in future. For now, I would recommend anyone interested in this subject to visit Reno, skip the casinos, and head directly to the Museum. This exhibition is on display until March 23, 2025.